We sat down with Nitinkumar Singh, Principal Engineer at Unique Group, who played a pivotal role in developing the Human Support & Safety System for MATSYA 6000, a project now shortlisted for the IMCA Innovation & Technology Project of the Year.

In this conversation, he takes us behind the scenes of one of India’s most ambitious deep-sea engineering milestones, sharing what it took to achieve DNV certification, overcome complex technical challenges, and deliver a system ready for deployment by the National Institute of Ocean Technology as part of India’s prestigious Samudrayaan Mission.

Q: What did you personally find most fascinating about designing a life support system for 6,000 meters below sea level?

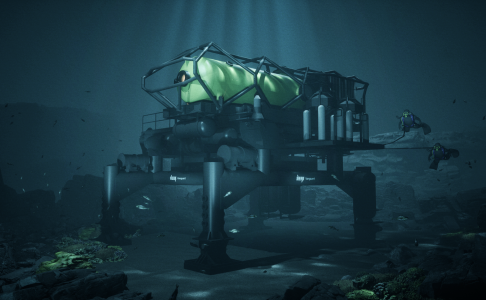

The most fascinating thing to me was how extreme the environment we were designing for. The system must withstand extreme external pressure, temperatures close to freezing, and total isolation from any chance of rescue at 6,000 meters. However, we must keep the environment steady, breathable, and comfortable inside the submersible. This implies that there is no room for error and each subsystem must function perfectly. It was cognitively challenging and incredibly satisfying to design a small, sturdy, and totally human rated life support system that could sustain life in such circumstances. It is comparable to space mission autonomy in many aspects, except instead of traveling into space, we are traveling down into the most hazardous regions of the ocean.

Q: From an engineering perspective, what makes this HSSS different from conventional life support systems?

In contrast to traditional diving or habitat-based life support systems, this system had to function completely independently inside the MATSYA 6000’s 2.1-meter internal diameter personnel sphere, supporting three occupants while fulfilling 12 hours operational and 96-hour emergency endurance requirements at depths upto 6,000 MSW. Without sacrificing safety or ergonomics, every component including oxygen delivery, CO2 scrubbing, humidity and thermal management, atmospheric monitoring, fire suppression, and redundancy had to be specially designed, reduced in size, and integrated. In contrast to traditional systems, which usually depend on accessible intervention or external support infrastructure, the outcome is a completely integrated, modular, and DNV compatible human rated system intended for extreme autonomy.

Q: What were the key design constraints of working within a 2.1m personnel sphere, and how did they shape your approach?

Space within the personnel sphere was the limiting factor. To provide accessibility, maintainability, redundancy, and sufficient physical comfort for three crew members who might stay within for days in an emergency, we had to install a full human life support system. This problem completely changed the way we approached engineering. We constructed a full-scale prototype mockup very early in the project so that we could physically walk through the plan, find interferences, and verify ergonomics. Long before the final assembly, that manual procedure helped us improve airflow, routing, control panel placement, and environment management. The end product is a space efficient, compact, fully integrated system that offers complete functionality without sacrificing crew safety or comfort. Effective engineering is more than merely technical in such small spaces, it must be really human centric.

Q: How does the system achieve the 12-hour operational endurance and 96-hour emergency capability?

The total endurance including normal and emergency duration was made possible by a well-designed set of interconnected systems. In addition to a high-capacity specialized CO2 scrubbing solution made especially for extended missions in limited spaces, we created an efficient oxygen storage and regulated distribution system. With the help of redundant safety subsystems, fire suppression and a fail-safe emergency breathing system designed for deep water Submersible use, an energy efficient environmental control and monitoring system regulates internal atmosphere of the pressure hull. When combined, these enable the system to maintain 12 hours of full operational endurance, while extra reserves offer up to 96 hours of emergency life support, guaranteeing crew survival even in the direst mission situations where resurfacing would take several days. Resilience is built into every aspect of deep-sea ecosystems; it is not an option.

Q: What was the toughest engineering hurdle during the project, and how did the team overcome it?

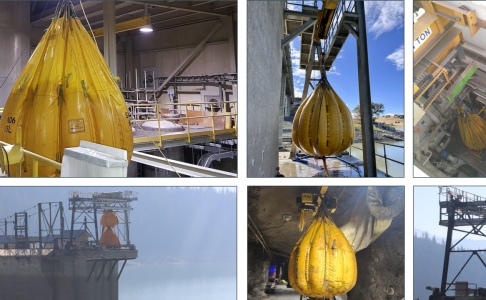

Every subsystem had its own set of difficulties, but the most difficult issue was integrating the entire human life support system into such a small space while fulfilling stringent DNV human rated life support system certification standards. Constant iteration, simulation, and practical prototype were necessary to achieve complete redundancy and compliance without compromising operational space. Using full scale mockups to physically test concepts, real-time technical reviews with DNV surveyors, continuous design refinement based on prototype trials and test results, we mostly relied on iterative engineering and hands on validation. The process was demanding but motivating, and it resulted in a successful Factory Acceptance Test. The team was really proud to see the system certified and in use.

Q: What was your role as R&D Engineer, and how did you guide the team through this mission-critical project?

I was given the opportunity to oversee the whole engineering process including R&D at Unique Group for the MATSYA 6000 mission’s Human Support and Safety System, from defining system architecture to guiding detailed design and verifying prototypes to final integration and testing. Making crucial technical decisions, preserving compliance with guidelines and requirements, and guaranteeing dependability and redundancy under limited space and stringent DNV guidelines were all part of my role.

For this R&D based project, I contributed to the development of several key subsystems that enabled the endurance and safety requirements of the mission, including the high efficiency CO2 scrubbing system, a compact dehumidification solution inside limited space, the optimized oxygen storage and controlled delivery system. I was also directly involved during the full scale Factory Acceptance Test, where the integrated life support system was tested inside the pressure hull. The system was accepted by the DNV surveyor during the first witnessed FAT, which was a proud moment for all of us and a strong validation of our engineering rigor, persistence, and safety focused design approach.

Guiding the system through every stage from concept to certified deployment required balancing innovation with absolute safety, and leading with clarity, discipline, and respect for the responsibility of sustaining human life at extreme ocean depths.

Q: What does this project mean for India’s Samudrayaan Mission and deep-sea research globally?

This project is a key milestone for India, placing it among an elite group of countries having deep-water Manned Submersible capacity. It opens up new avenues for sophisticated oceanographic studies, strategic underwater capability, deep-sea mineral study, and scientific exploration. Beyond the national accomplishment, it establishes an outstanding standard for compact, dependable life support technology under harsh circumstances and demonstrates that top-notch engineering can be created and constructed domestically. It’s a momentous occasion not only for the mission but also for India’s deep-sea engineering and research future.

Q: What does being shortlisted for the IMCA Innovation & Technology Award signify for you and the team?

For me and the team, this recognition reflects the vision, perseverance, and engineering discipline that went into the project. Being acknowledged on a global stage validates not just the technology, but the culture of innovation and commitment we strive for at Unique Group. It honors the continuous effort behind every iteration, test, and design decision. It also celebrates the capability of a small, highly focused engineering team that successfully solved one of the most demanding life-support challenges proving that dedication and teamwork can achieve what many consider impossible.

Q: What would you tell young engineers who dream of building innovative systems for extreme environments?

Engaging with young engineers is something I really enjoy, whether it is by mentoring them through academic projects or imparting knowledge from practical engineering challenges. Like physicians and educators, I firmly think engineers are essential for creating a better, more sustainable world. Beyond merely resolving technological issues, we have an obligation to push boundaries, innovate ethically, and enhance people’s lives.

I frequently advise young engineers to pursue tasks where failure is not an option and to work in environments where their curiosity makes them feel a little uneasy. These are the settings that foster resilience, creativity, and discipline. For R&D enthusiasts, Prototype frequently, have patience with complexity, and have more faith in physics than in assumption. Extreme environment engineering is never about big ideas alone, but it is built on strong fundamentals, rigorous testing, and the courage to keep improving. If you adopt that mindset, the world will present opportunities worthy of our ambitions.